How might one fathom the vastness of the biggest explosion in human history, the Krakatoa eruption of 1883? Can textbooks ever adequately convey the immensity of such events, the destruction they wreak and the regional and even global fallout they produce?

The Krakatoa catastrophe only took place 135 years ago, and many of the resulting geological features are still in plain sight. Thus, our response to the educational challenge was to take the students on-site and immerse them in the landscape formed by that catastrophic event. We organised a Tembusu STEER voyage with the aim to visit the Krakatoa archipelago—our “Recess Week Volcano Voyage”—for 9 NUS students, 2 exchange students and 2 alumni. We boarded the 78-feet staysail schooner “Four Friends” in Jakarta on 24/2, set sail on 25/2 in the afternoon, and reached the Krakatoa archipelago in the Sunda Strait on 26/2 in the early morning hours. It was the ninth voyage by the NUS Seafarers, a Provost Office initiative that so far has taken 101 students and 8 alumni on immersive learning experiences in Indonesia and the Philippines, where they learned about the economy, society, biodiversity and geography of these maritime nations.

The tallest island of the Krakatoa archipelago is often partially hidden by clouds; it comprises the southern flank of the original pre-1883 Krakatoa volcano, an island today known as Rakata.

The best part of the trip for me was being able to see Krakatoa itself up close after having read and heard so much about it. The scale of the place was astounding and I still find it hard to believe that I was at the site of such a significant event.— Grace Tang, 4th Year, Geography

The following three days provided ample opportunities to study the archipelago, consisting of Rakata, two smaller Krakatoa remnants called Rakata Kechil and Sertung, and Anak Krakatau, a new volcanic island that emerged from the sea in 1927 in the vast seafloor hole created by the explosion. We explored the sea life that has re-established itself after the catastrophe, including several coral reefs and a large pod of dolphins, while snorkelling and navigating. We hiked through the tropical forest of Rakata and Rakata Kechil, which has grown back in the past 135 years on the fertile ash that the explosion deposited on the surrounding islands. We established the heights of the peaks of Anak Krakatau (302m) and Rakata (810m) using sextant, GPS, radar and high school trigonometry.

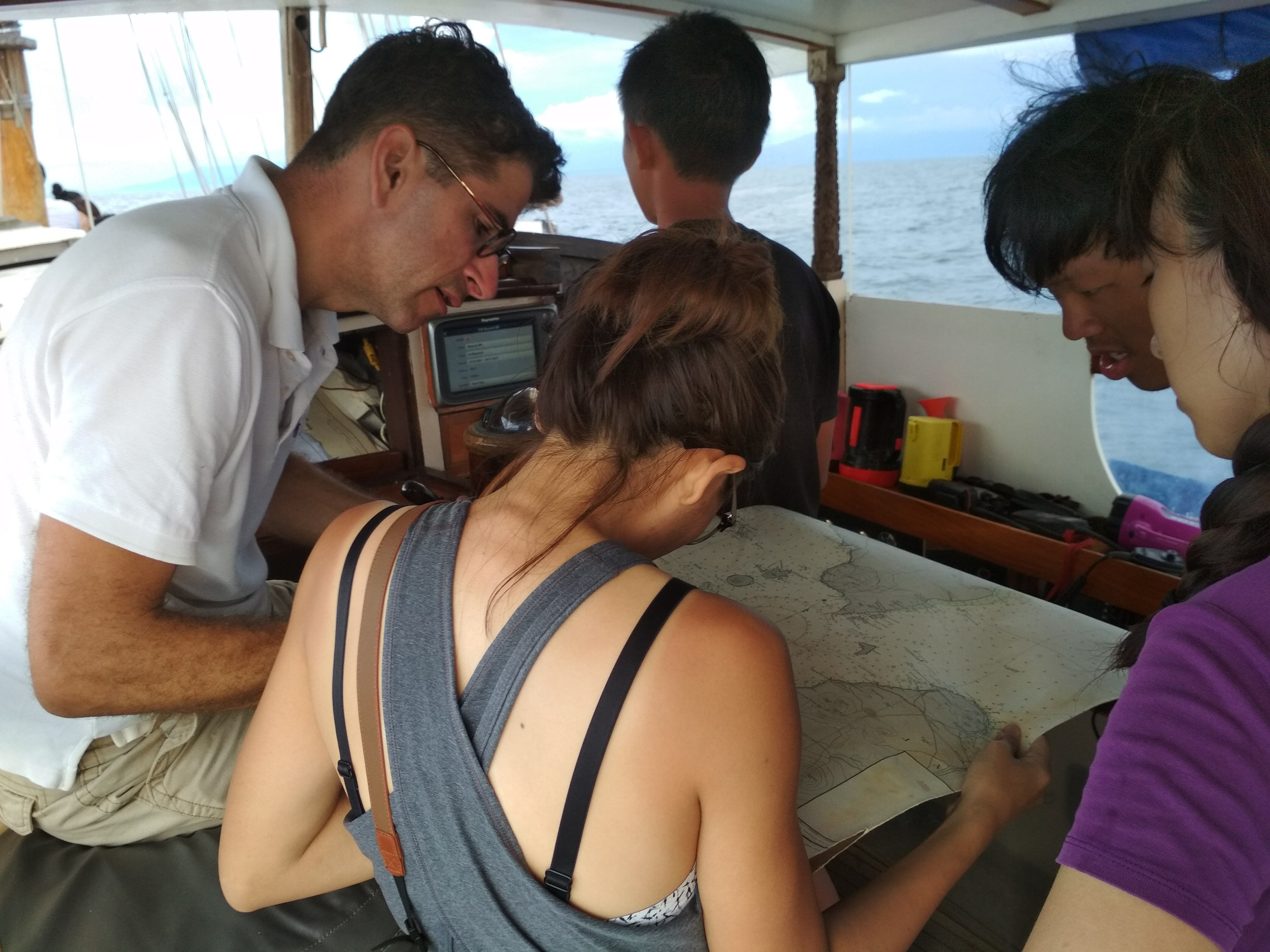

We examined rock samples from all four islands and conjectured their likely origin. While kayaking, we discovered pumice (volcanic rock) from recent eruptions, floating (yes, pumice is often lighter than water!) and washing up on the shores of the islands. We studied modern and historical maps and charts to complement our first-hand experiences.

The voyage on board the Four Friends showed me that geography is everywhere, you just need to be inquisitive and daring. As we worked together and started to believe in each other as a crew, and with our eyes set on the horizon, we confidently sailed forward unto discovery and adventure.— Nicholas Seow Wei Ming, 4th Year, Geography

Then, on 28/2, our third day in the archipelago, the stars aligned. A steady northerly monsoon wind exposed a cloud and gas-free ascent path on the northern flank of Anak Krakatau. The seismic readings that we monitored using a satellite phone and a Singapore-based collaborator showed benign levels of volcanic activity, and visual inspection of the crater elevated our hopes that a visit of the summit might be possible that day. We landed on the island using our launch and kayaks and made our way to the foot of the mountain through a vast and rugged lava field.

The second author—invariably called “Dr John” by the students—scouted out a suitable route for our ascent, while the remaining team further inspected the lava field. Chu Qinghao (2nd Year, Computer Science + USP), Daren Lau Jia Ching (4th Year, Industrial and Systems Engineering) and the first author decided to follow in the footholds that Dr John had prepared for them. Continuous VHF communication with the mother ship and with each other during the ascent enabled us to react to any possible changes in the cloud pattern over the volcano and other signs of danger. The summit provided breathtaking views of the seascape towards Sumatra. Breathtaking in quite a different sense was the direction towards the caldera! We saw a complex amalgamation of igneous rock and ash riddled by a myriad of tiny holes from which hot water vapour and volcanic gases oozed. We flew a drone over the caldera and took movies and pictures, before carefully descending the same path that we ascended.

What better place to grasp the scale of the 1883 Krakatoa explosion than on top of the crater of Anak Krakatau, which grew from the depths of the sea at the site of the original volcano, with vapour and gases emerging from the ground on which we stand?

A multisensory learning experience in nature’s classroom. Spontaneous activities undertaken during the voyage encouraged experimentation and calculated risk-taking; these can hardly be learnt in the safe and organized learning environment in university. I feel connected with nature again.— Wong Li Ching, 2nd Year, Business + USP